.png)

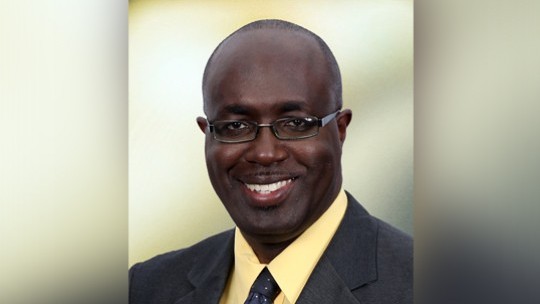

Gary Allen, Managing Director of the RJR Communications Group, has been a media professional - in journalism and media management - for three decades. He started as a St. Mary based correspondent for The Gleaner newspaper in the mid-1980s before joining Radio Jamaica a few years later.

In a wide-ranging interview with Earl Moxam, he recently recounted many aspects of his media career. In part two of the interview, detailed below, he discusses his departure from RJR in the mid-1990s and the experience he gained during that period, before returning to the Lyndhurst Road based media company, more than a decade later.

EM: In the mid-1990s you had a new opportunity and challenge - that of heading up a new newsroom at CVM. Take me back to that, in terms of, first of all, what the opportunity represented, and whether this was an intimidating challenge at the same time.

GA: Going back to where things were in my career at the time is important. Miss (Janet) Mowatt had left; David Ebanks was the Executive Editor for a short time, so he was in charge of the administrative running of the newsroom and Jennifer Grant was the next in command. David gave up that job because he really was not an administrator, was not interested in doing administration… Jennifer Grant the person who was named News Editor at that time, and Michael Sharpe and myself were appointed assistant news editors. So, by early 1992, all of a sudden, after being at RJR for four years, I had moved into a position of junior management, as Assistant News Editor. Jennifer was quite young, Michael, quite young; I was younger than both of them. But I wanted now to do things to impact the budgeting, to impact the content, to impact the structuring of how we do things and so on; I started getting interested in that. So, recognizing that, with young people in the mix, in management, that if you’re going to get to that kind of influencing point in designing and doing things, when CVM that got a license in 1991, I think, decided that it was time to move into the establishment of a newsroom – and I think Patrick Harley was there for a short period of time – and then they advertised, I applied and I got the job. I remember Lennie Little-White was the person who had discussed with me all the ideas that they had.

Going to CVM was now a very interesting part of my development. The ideas I thought I had, I had a chance now to design them and put them to work. And so, a lot now was in how do I do television? I had worked in radio all along, so I essentially immersed myself into reading all that I could about TV newsrooms, TV management, TV opportunities. When I went there I tried to learn from everybody. I would go out with the engineers to see what they did at transmitter sites; I would be in the production department to understand editing and I would go out on shoots and so on, just to learn that very quickly. And then the structuring of it; I would just read about different things – what the BBC structures were, what the CNN structures were, and out of that, put together a system. (We) started small with short newscasts called News Brief; I remember, at 6.25 in the evenings, five minutes, until we grew to deciding that we were going to do a half-hour investigative programme once a week, called Probe. Then we went on to doing a weekly news review, before we got into some big assignments. I remember the Pope (John Paul II) visited Jamaica, and that was one of the major stories that we had to cover. Even covering Champs (the annual Inter-Secondary Athletic Championships) at the time was something that the news people did, with one sports specialist in Ian Andrews at the time. So, we learnt everything and understood how everything worked. So, when we came to the point of launching a seven day a week newscast, it was a newscast with a difference, that took a different focus on how we did things.

And that, I think, caused me to get very quickly to a point where I wanted to find out if what had been constructed was a structure that could work. Could it stand on its own if I wasn’t there seven days a week, as I was at the time, running from here to there, holding things together? Was the team strong enough? And so that was in the back of my mind when an opportunity came up to work for the Caribbean Broadcasting Union as its Programmes Operations Manager, which included news, programming and production. I had already developed a strong interest in things Caribbean, having covered, up to that point, probably about six or seven Caricom summits – the first one in St. Kitts in 1991, when Michael Manley returned to Caricom after a very long layoff. And I did different summits after that, including some regional economic conferences, one of which coincided with when Abu Bakr was released from prison, and… I remember going and sitting on Frederick Street at the front of the prison for about eight hours until the prison doors finally opened and this man came out, and to hear how the Muslims that were there cheered and so on. I had a good understanding from one of his wives who was there for most of those hours, and we talked about what the experience was in a family that I had absolutely no idea how a Muslim family worked. And later on, I was to meet Abu Bakr himself and have a long discussion with him in Barbados when he was honeymooning with this third wife. And he actually was telling me a lot about it and trying to encourage me to read more and to look at the faith as an option. So, those kinds of things created a different me, in understanding of things Caribbean, of different perspectives, not just of religion and politics, but to really get into the diversity of what exists out there. So, I believe that the experience from the (RJR) newsroom, to creating a newsroom at CVM, and then moving on, letting it go, and seeing that it stood up and was able to function without me was more a tribute to the fact that the people who were there were the right choices to have made, and that they were competent and capable enough to stand up.

EM: There’s one criticism that I heard quite a few times about the approach used (at CVM), which was that it helped to foster the roadblock culture in Jamaica. Is that something that you would push back at?

GA: I don’t know that I could honestly push back at it and say there was no impact. I think I would add a different context to it, because before that there were roadblocks that were happening. The biggest roadblocks I’ve seen in Jamaica was when we had a gas strike. I remember walking seven miles from Change Hill down to school down in Highgate and seven miles back home… in 1979. That probably is still the mother of all roadblocks that the country has seen. So, I think that the roadblock culture was always there. I believe what has to be acknowledged though is that, at CVM, there was a decided effort that we made to move away from the microphone presentations, especially by politicians and the few business leaders who were speaking out at the time.

And so we moved away from covering breakfast, lunch functions and dinner speeches, and simply having a newscast of those, and we went to the communities to find out what people’s issues were. And that led to people becoming accustomed to seeing themselves with their issues on TV more, and yes, it escalated into a component of what already was a roadblock culture that existed being one that became more frequently used to gain attention.

I think a part of the challenge with that is that many of the political representatives and the State agencies would ignore people unless they blocked the road. And when they blocked the road then it became a news story that we covered, so you got into a chicken and egg situation at that level. But I would say that there was a road block culture before? Was it intensified during the early years of CVM and when our news room was doing that? Yes, it intensified, in the same way that what also intensified was a lot of coverage of police operations. Because we did have embeded reporters at that time who went out with the police and who were able to film police on operations. There was a group that was called ACID (Anti-Crime Investigative Detachment), and then their name was changed to the Special Anti-Crime Task Force. And I think that their operations, we had looked very closely at the things they were doing at the time. So yes, that also created a great influx of stories about police operations in the newsroom as well, or in the news product as well.

EM: Was that critical reporting, though, on how they operated?

GA: There was a bit of that but to be honest but it was more about what they were doing in terms of they are gone to this place. They had found these suspects, these guns or they had taken these people into custody but yes it also went into some of the issues of whether or not people’s rights were being abused, because what was something that was seen as normal policing, and being reflected as such, when human rights organizations, such as the Jamaica Council for Human rights led by Flow O’Connor then, who is one of those persons who has not gotten as much credit as she should have gotten for raising the human right issues consistently and tirelessly about police abuses, long before they had the BSI (Bureau of Special Investigations), long before they had INDECOM (Independent Commission of Investigations), long before it became fashionable to question a lot of these things. I think that the presentation of a lot of those police operations gave an insight which people like Flow O’Connor then drew to the attention of the public, that this was not okay. So I think, in a way, while it may not have been the intended approach at the beginning, it also led to another critical thinking and discourse, nationally, about these things.

EM: That transition from being a reporter to becoming a manager, and not just a manager of a news room, but ultimately a manager of news organizations and a media manager, as you are now in Jamaica, how difficult was that transition?

GA: It was very hard I think it took me about eighteen months to two years to resist the temptation not to go into newsroom every day. It was just something that was just in your blood, and it still is, and, while I don’t get up and go every day, I consume the news critically and I have very strong opinions about it which I share with the News Editor, and which I shared quite openly about how I think we should look at stories, stories that we are not investigating, where there have been issues with how we have presented things, issues of balance and accuracy and so on; it’s still there. But it took me almost two years to get to the point where I didn’t get up and go in the newsroom on a particular day and spend time there. So, when I was first the manager, I was managing early morning, working in the newsroom during the day, up to news time, and then going back to do management work until one, two o’clock in the morning.

EM: That was in Barbados?

GA: Well here too! It happened with CVM as well. Putting CVM together… While I was the news manager I was working with a very young team, because we started with a young team before Milton Walker was one of the most experienced people that we brought on, and then I think Ingrid Bryan from JBC at the time; Ian Andrews in sports. But before that it was all unknown names in journalism, so there was training that I had to be doing and there was leadership by example that had to be done. So I was the manager but I was ostensibly the chief reporter out there doing things as well, as a part of that training and development process. And then going on to Barbados, it was a very different process; a very laid back society, don’t push much on the news, very contented with what they had. They used to just to do a news exchange at the Caribbean broadcasting union (CBU) and they were satisfied with that. Looking at that, and knowing that a newscast is what people watch, is what led to me then getting us together to start Caribbean Newsline which is still on air now and still produced for the region, And then to start Caribbean News Review and to start Caribbean Business and to start a show that Julian Rogers did - Talk Caribbean. So, we did different programme developments in that regard. So, it is the journalism in me while I managed which still led to the development of these things. So it wasn’t a separation and movement from journalism to management and management meetings and writing reports and doing budgets, that was the thing. It was still doing the journalism and the training, plus taking on those things.

EM: How much of the journalist in you is excited about the possibility or the prospects of an RJR Gleaner merger, in terms of the possibilities inherent in that merger?

GA: It’s interesting and exciting from two different stand points. One of them is that I believe very, very clearly... that there has to be editorial differentiation in the organization, that if the merger goes through, would happen. One is that RJR’s reporting of the facts of what happen on a day to day basis and investigation things and bringing that investigating to the fore and calling people to book to analyze and give commentary on it. That is one type of journalism which I think has served RJR well for its 65 years. I don’t think that we should trifle with that. The Gleaner has had a position taking, editorial driven: “This is good for Jamaica! This is our position on this topic. This is what we think should happen with these laws!” That, I think, has been good for The Gleaner and has served The Gleaner well. I do not think that putting that Gleaner structure on RJR and is good for RJR, and I don’t think that putting RJR’s reporting and analysis structure on The Gleaner and abandoning the position taking would be good for The Gleaner. So I think that there will have to remain a strong differentiation in the editorial direction of the organizations in that way.

EM: And you think the public out there will make that distinction, knowing that the two companies have merged?

GA: I think some people will not make the distinction, but I believe that it will be clear from the output that there is a distinction and that is what will be the final point that one has to judge by. Do you see RJR becoming more of a position taking entity? I should think not! Do you see The Gleaner becoming more of a just a reporting of different sides of the story without taking a position? I would think not. So, I think, if we get there, that is something that the public will be able to discern. Yes, there will be some people who will say “Gary Allen is behind telling this one what to do and that one what to do.” That has been a criticism all along about things that 95 per cent of the time I have not even heard as yet, and the other five per cent of the time, I hear it in the news like everybody else. But you have to be strong and clear in your own mind about the integrity that you bring to it, not to be bothered and swayed by the people who will think that there’s this agenda and this hidden hand being manipulated by whoever is in charge doing that.

I think though that there is an excitement that we should anticipate in the journalism, that I find really, really a good prospect. I think we can do some editorial collaboration on things that have gone in Jamaica and things that will come in Jamaica, that both can give Jamaica more out of it.

The access to the archives of The Gleaner is going to be hugely beneficial in developing a new product that Jamaica has not yet seen. What was Jamaica like? I think that, once this coming together takes place, our Emancipation Day programming will be different, because we’ll be able to relive, through the Gleaner archives what was happening in Jamaica between 1834 and 1838. When you think about 1938, 1865; what happened in the lead-up to Morant Bay, what were we reporting, what did we say people in the streets were saying and doing… Can you imagine telling people in West Africa the stories of what was happening in the last days of slavery with their ancestors in the largest English speaking Caribbean territory? Those are stories that will be of global appeal. So, I see that as an excitement! I see a journalistic product, which is a Gleaner-RJR, or Gleaner-TVJ special reporting, and special documentary presentations. I see that as the excitement that will come, not whether or not we are going to be sitting down and deciding that on the front page of The Gleaner and The Star, and on TVJ’s news and on RJR this is the one position that we are going to carry. That is not excitement; that is not fun.

NOTE: You may access part one of this feature here

.jpg)

All feeds

All feeds